The most common question I get from entrepreneurs and executives:

“What do you think our company is worth?”

If you’ve ever wondered how to determine that for yourself, keep reading. I’ll explain.

In “typical” finance, the value of a company (or asset) is usually determined by a discounted cash flow model. Basically, you have a spreadsheet that says how much cash flow the asset is going to produce over its lifetime.

Then, you discount the value of all future cash flows to today to account for the risk and uncertainty of that forecast coming true.

For example, you say to me, “Hey Oren, I’m going to open another 10 locations of my coffee shop concept…and launch my new Double Shot Redeye with shade-grown wild Kopi Luwak …”

Hmmmm. Maybe you can, maybe you can’t…but I just don’t have enough evidence to believe in that plan. But I do think you can open five stores in the next year.

So I discount your plan to “What I think is really going to happen…”

And if I’m the investor, well, we go with my numbers. And now we have a priced deal, otherwise known as VALUATION.

This value is a compromise between what you say is going to happen in the future in the extreme case, and what I think is going to happen in the base case.

But that doesn’t explain all these “Unicorns” like running around Palo Alto, breaking the valuation “rules” I just gave you.

Unicorns like Dapper, Gong, Airwallex, Hopper, Ramp, and a hundred other companies you never heard of.

These deals are carrying or have carried above $1B valuation, but it’s NOT because of cash flow.

Those Unicorns are valued as a multiple of some metric – whether it’s revenue, user growth, monthly recurring revenue, or even EBITDA – you’ll notice the larger the number being multiplied is, the larger the valuation is.

Which makes sense, when you think about it.

The more mature the company is – or the faster it is growing – the more likely it is that the forecasted results are going to come true.

And if you want to know the trick to having control over your valuation, it all revolves around how much investors believe your forecasted results are going to come true.

Here’s a real-world example – the $200m advanced manufacturing facility I’m building in Dallas, Texas with my partner Breton SpA – the global leader in engineered stone manufacturing technology.

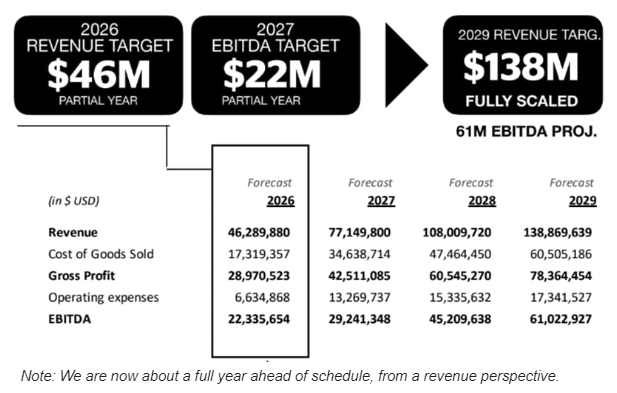

When we started raising capital in our Series A1 – which oversubscribed in a day – here was my original forecast.

How did I come up with this forecast? I spoke with our partners at Breton – which has built 80 other factories – and found that this was the model they’d already succeeded with many times.

In fact, the most recent factory they built went from $0 to $100m in revenue in three years (once built.) It generates around $24m of income for shareholders.

Now let’s assume I could “copy and paste” this factory, put it in the United States, and turn it into a publicly traded manufacturing company

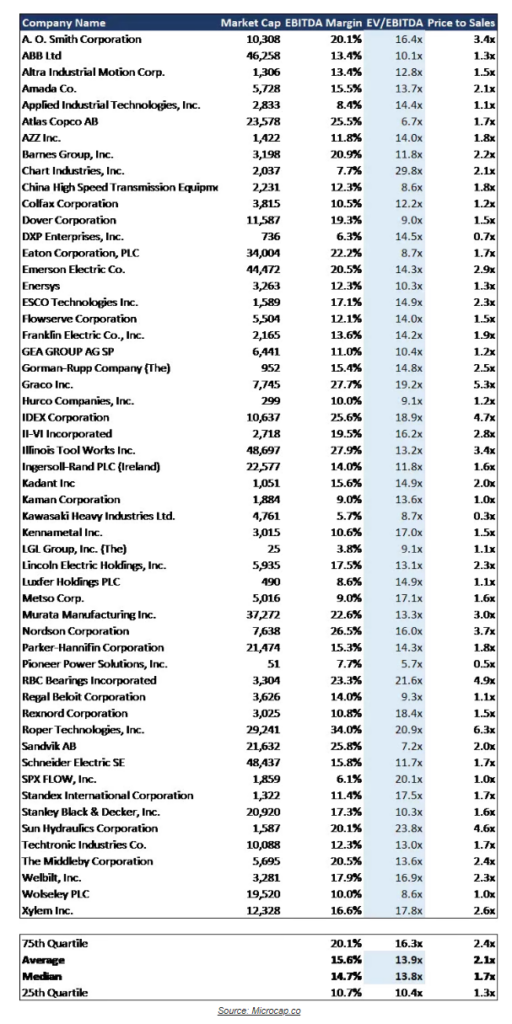

So how much is this factory worth? It depends on who the buyer is, what the market comparables are at the time, and what the overall market sentiment is (i.e. the forces of supply and demand inevitably determine price).

But to keep things simple, let’s just say an asset generating $60m of EBIDTA, which is our plan, could be reasonably valued at a 12-18x multiple – which would be $720m – $1bn in market cap (see chart for comps)

What factors – aside from pure supply and demand – would justify a higher multiple?

Your company’s value all comes down to how much investors believe in your forecast. If you think of each deal point as another card you have in your Royal Flush hand in the Game of Money, the more of these “playing cards” your deal has, the more you “de-risk the deal” and increase the certainty of the forecast coming true.

If you’ve got a proven track record of hitting forecasts on time and on budget, investors reward your management team with higher valuations.

Even better? You’ve got a track record of outperforming your forecasts and delivering results ahead of schedule and below budget.

But I still haven’t entirely answered the question of “how do I price my company” at any stage, even if it’s pre-revenue. To answer this, I’ll have to go back to the discounted cash flow model, risk, and uncertainty.

If an investor in my high-tech factory could reasonably assume the forecast I provided was going to come true – exactly as I’ve presented it, with no variation – that would be a risk-free investment.

Assuming the forecast was guaranteed – I’d snap my fingers and create a $1 billion asset by 2029. However, I can’t do that, so this isn’t a risk-free investment.

And for that reason, the investors want to be compensated for the risk they are being asked to take, in the form of a discount to the forecasted $1 billion valuation.

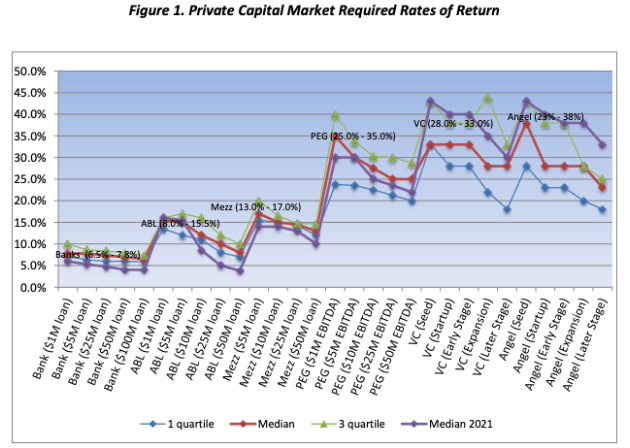

We can see this fact represented in the annual Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project report via the expected returns investors are looking for – the earlier and more risky the investment, the higher the rate of return.

The cost of capital for privately held businesses varies significantly by capital type, size, and risk assumed. This relationship is depicted in the Pepperdine Private Capital Market Line. Source: Pepperdine

When I raised the first tranche of capital – our Series A1 that oversubscribed in one day – my team invested because they had a close personal relationship with me.

At that time, the key “playing cards” I had in my deal were a great story, a proven business model, and rights to the intellectual property supporting the product I was selling.

Here’s what we didn’t have: a building (or land, for that matter,) equipment contracts, raw materials, and a management team with employees to run the whole thing.

Sure, these were my friends, and they wanted to support me. And sure, I had already put in $1 million of my own capital and four years of my time.

But A LOT still had to happen for my original forecast to come true.

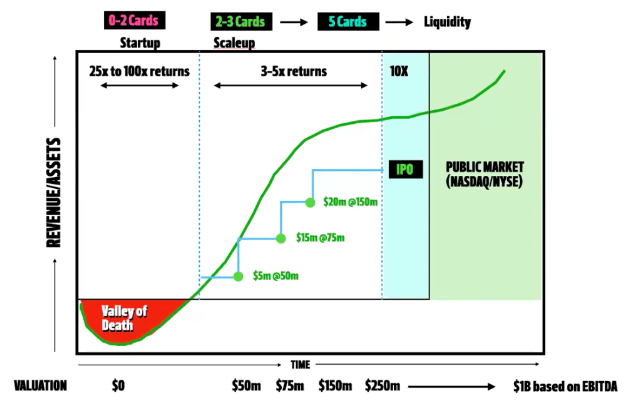

For that reason, they got to come in at the lowest price.

“Hey, that’s great Oren. You’ve got some rich friends who gave you some money for your deal. What does that have to do with me investing in this current round?”

As the sponsor of this deal, one of the things I know my investors want is to see the value of their investment go up…and ideally, go up quickly.

In public markets, you’ve got a real-time stock ticker telling you what the shares are worth.

But in private markets, the only time the deal valuation goes up (or down) is when a new round of capital is raised.

In order to control my cost of capital and protect the value of equity for early investors, I needed to have a plan for constantly increasing the valuation as we hit major risk-reducing milestones in the project.

It looked like this.

In fact, if you’re looking at the “gameboard” in The Game of Money, this is it:

Between the Series A1 price and the current Series A2 price, here’s what I achieved:

Based on all these major milestones being hit, we decided to raise the price. Since we’ve opened the Series A2, here’s what we’ve achieved:

Now that we’ve hit all of these milestones – and dramatically accelerated our forecasted results – we believe it more than justifies the step up in price, as we have significantly reduced the risk by hitting these milestones.

Determining the value of a company isn’t just a matter of crunching numbers.

It’s a whole-picture analysis of the hand the business holds.

Forecasts, risk assessments, and investor confidence all have their roles to play.

However, you can stack the cards in your favor by hitting milestones early, which reduces the risk to your investors and increases your valuation.